Main conclusions from the evaluation of the GGB proposal for 2021-2023:

Key conclusions and recommendations

The draft general government budget for 2023 to 2025 was submitted by the government amid Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine and the energy crisis, the negative impacts of which are reflected in a significant deterioration of both the macroeconomic and fiscal development outlook. The resulting long-term burden on public finances is estimated at as much as 0.7% of GDP. Without the funding from EU funds, the Slovak economy would not grow next year at all. Due to the war, the economy will be underperforming, while the risk of being hit by a recession next year has increased considerably.

The draft 2023-2025 general government budget is the first budget proposal presented after the entry into force of the legislation that has introduced expenditure ceilings as a fiscal rule. The expenditure ceilings are a key budgetary tool to achieve the long-term sustainability of public finances and was supposed to apply for the first time to the 2023-2025 general government budget. The current draft budget was not prepared in compliance with the expenditure ceilings since the Ministry of Finance and the CBR have still not agreed on the final methodology[1] for calculating, updating and evaluating compliance with the ceilings. Therefore, the Council could not calculate the ceilings and submit them to the parliament for discussion as required under the General Government Budgetary Rules Act.

Assessing the fiscal policy is also important in view of the projected amount of the 2022 gross debt exceeding the highest sanction bracket and termination of the two-year exemption on the application of sanctions under the third, fourth and fifth sanction bracket for the new government on 5 May 2023[2]. The government has not clarified how it plans to address these sanctions if the 2022 debt proves to be in excess of the fifth sanction bracket. According to the CBR, the existing situation cannot be resolved by solely formally complying with the applicable rules, or by directly circumventing them, but they must be appropriately adjusted through the adoption of the proposed amendment to Act No. 493/2011 on fiscal responsibility, designed to update the debt break mechanism and bring it into compliance with the expenditure ceilings.

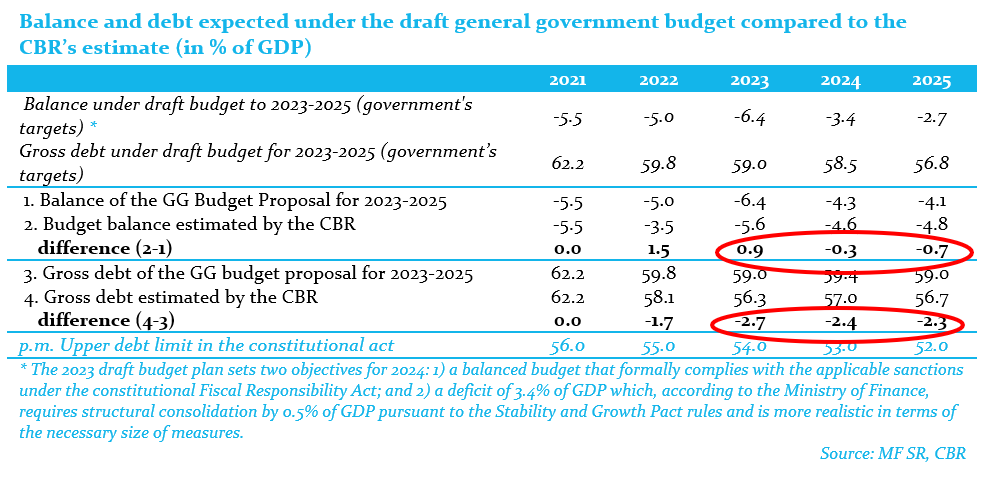

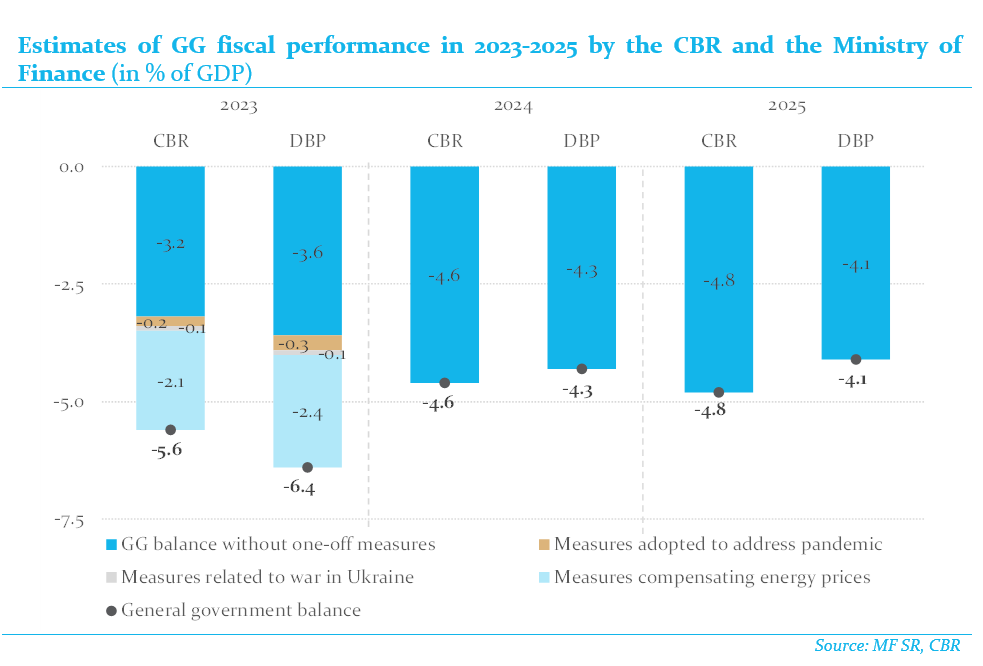

Against the general government deficit originally budgeted at the level of 4.9% of GDP in 2021, the government currently estimates the deficit to increase to 5.0% of GDP. For 2023, the budget proposal assumes a year-on-year increase in deficit to 6.4% of GDP. The presented budget expects a gradual decrease in deficit towards the level of 4.1% of GDP by 2025. The government intends to achieve a 3.4% of GDP general government deficit in 2024 and, subsequently, at 2.7% of GDP in 2025[3], but there are currently no measures prepared for those years that would result in meeting these goals.

The draft budget assumes a decrease in gross debt from 62.2% of GDP in 2021 to 59.8% of GDP in 2022 and a subsequent further sharp decline towards a 56.8% of GDP level by the end of 2025, relying on the fulfilment of fiscal objectives that are not supported by any measures. This decline is mainly driven by a high pace of inflation expected in the upcoming period. Irrespective of the discontinuation in debt level growth in 2021, starting from 2020 the debt has been above the upper limits of sanction brackets under the constitutional act and will remain above this limit throughout the forecast period, according to the Ministry of Finance.

The purpose of the CBR’s opinions is to offer an independent view on the budget and assess whether the fiscal policy setup is sufficient in terms of achieving the targets set and, at the same time, to identify potential risks which need to be eliminated through the adoption of additional measures. In line with its mandate, the CBR also assesses whether the current budget creates conditions to ensure the long-term sustainability of public finances and to meet the national fiscal rules. To that end, the CBR wishes to highlight the following key conclusions from its evaluation:

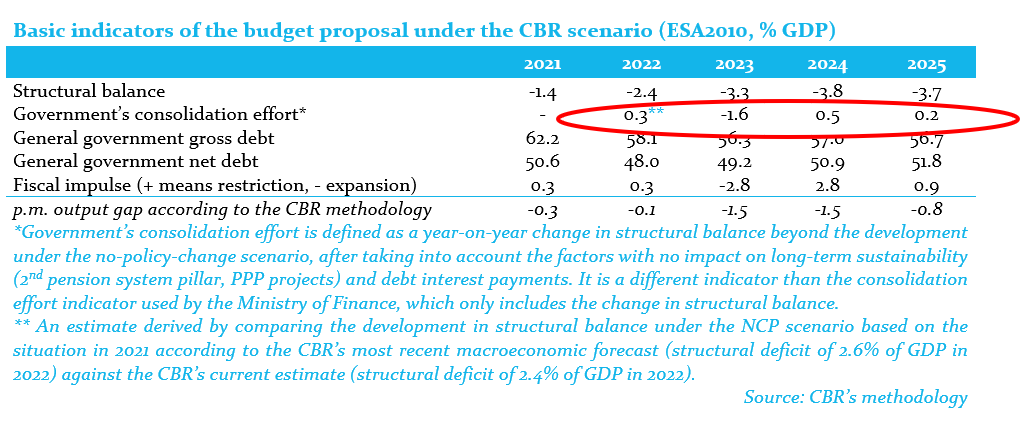

- The baseline year for the preparation of the 2023-2025 general government budget is 2022. If no additional measures are adopted by the end of the year, the Council believes the 2022 deficit may be 3.5% of GDP only. This represents a considerably better starting position (by 1.5% of GDP) for the 2023-2025 period than as currently estimated by the government. The positive risk is mostly associated with the overestimated spending of current and capital expenditures included in the government’s estimate compared to the actual development. We currently estimate the government’s consolidation effort to stand at 0.3% of GDP this year.

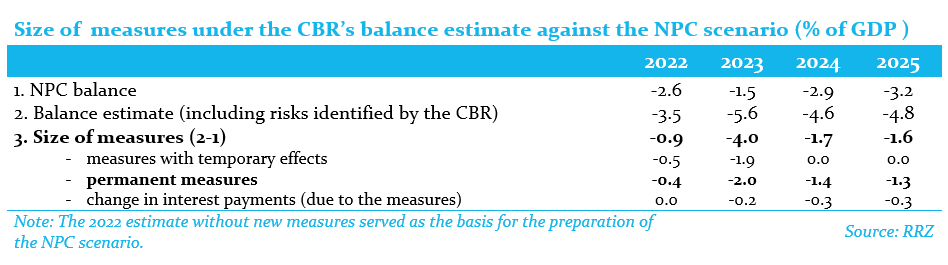

- Under the no-policy-change scenario (without new measures approved in 2022), the general government deficit would increase – from the 2022 level of 2.6% of GDP followed by a temporary decrease to 1.5% of GDP in 2023 – to 2.9% of GDP in 2024 and 2% of GDP in 2025 (cumulative structural deterioration by 0.1% of GDP). This development is mainly associated with the deterioration in macroeconomic development caused by Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and the energy crisis, and a decline in real and increase in nominal parameters driven by robust inflation. Viewed by individual years, the effect of high inflation rates on public finances will be shifting since, unlike revenues, a large portion of expenditures responds to the growth in nominal economy with a delay. A temporary improvement caused by the growth in tax revenues in 2022 and 2023 will be fully erased by the growth in expenditures linked to the high inflation rate in subsequent years.

- The Council estimates that the 2023 deficit may be as high as 5.6% of GDP. The deficit level estimated by the Council for 2023 is thus 0.9% of GDP lower than the one projected by the government. From this point of view, the submitted budget for the next year can be assessed as realistic even though negative risks as well as positive developments in some items have been identified in the budget structure.

- The Council considers the creating of reserve funds of 3.4bn euros to help address high energy prices a prudent measure. However, it is important that the funds are only spent on a temporary and targeted support and the government should give transparent reasons for this particular type of assistance and its size. If, due to a better-than-expected development, it will not be necessary to provide aid in the full allocated amount, or if these expenditures are partially covered by EU funding, the remaining funds should automatically be saved because the current rules formally allow the government to use them for other purposes, as well. On the other hand, if a higher amount of compensations proves necessary, the parliament should increase this reserve.

- In the upcoming years, the Council estimates a reduction in deficit to 4.6% of GDP in 2024, and to 4.8% of GDP in 2025. In particular in 2025, the estimate is 0.7% higher than the budget balance according to the Ministry of Finance; therefore, the budget prepared in those years cannot be considered realistic. Furthermore, assessed against the declared targets, the government lacks specific measures in the amount of 1.2% of GDP in 2024 and 2.1% of GDP in 2025.

- According to the CBR’s estimate, the permanent measures cumulatively increase the deficit by 0.6% of GDP (approximately 740 million euros) over the 2022-2025 period. Their net contribution to the permanent change in the general government balance will be negative in 2023, at 1.6% of GDP, mostly due to the adopted legislation; this, however, will partially be offset by the development in the next two years (improvement by 0.05% and 0.2% of GDP, respectively). The effect of deficit-improving measures, mainly in 2024 and 2025, is mostly associated with the CBR’s assumption that local authorities will be forced to offset the shortage in revenues caused by legislative changes and the increased spending on compensations and intermediate consumption not covered by revenues by permanent cuts in operating expenditures (contribution of 0.3 p.p.). If this assumption did not materialise, the government measures would contribute 0.9% of GDP in total to the deterioration of the balance between 2022 and 2025. By contrast, if the new revenue-side measures, which have already passed the first reading in the parliament, as well as an increased support to medical doctors are approved, the negative impact of the measures would fall from 0.6% to 0.5% of GDP.

- The analysis of adjusted expenditures shows that the growth in expected current expenditures is 1.8 p.p. slower in 2022 than the economy’s trend performance. In 2023, on the other hand, they outpace it by 2.3 p.p. It means that, cumulatively, the adjusted current expenditures grow in line with the economy’s trend development in 2022-2023. The 2023 expenditures are thus catching up with their slower increase in 2022. Given the strong need for consolidation in the medium term, it is desirable that the pace of growth in (adjusted current) expenditures be lower than economic growth.

- Based on the estimate of the development in general government balance, the CBR expects that the gross debt may amount to 58.1% of GDP in 2022, a year-on-year decline of more than 4 p.p. from its historically highest level of 62.2% of GDP in 2021. In the subsequent years, it would decline to reach 56.7% of GDP by the end of 2025, including due to the projected significant inflation and a gradual reduction in the cash reserve. With respect to the gradual decrease in the thresholds of sanction brackets, this would mean that the 2025 debt remains nearly 5 p.p. above the upper limit of debt break. The net debt would stand at 48.0% of GDP at the end of 2022. Due to the absence of consolidation measures, the CBR expects the net debt to gradually rise to 51.8% of GDP by the end of the medium-term horizon (the end of 2025). The new permanent government measures increase the debt by 3.4 p.p. over the period until 2025.

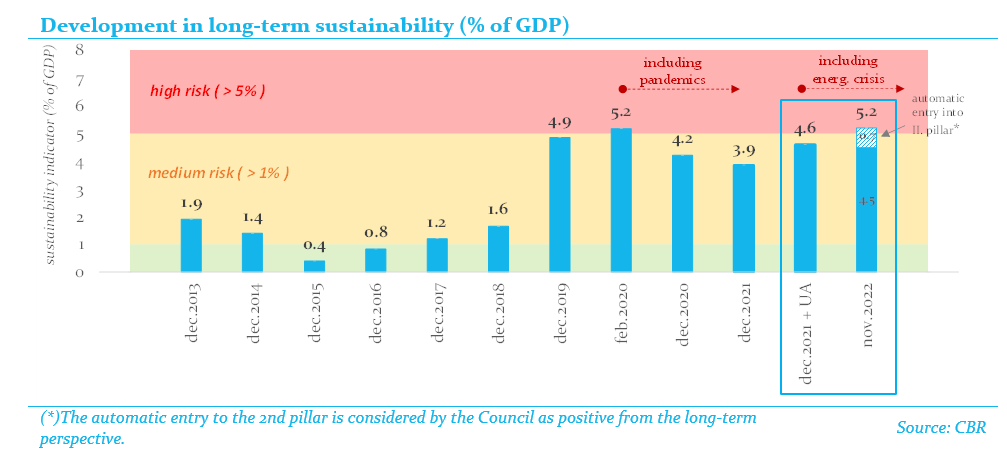

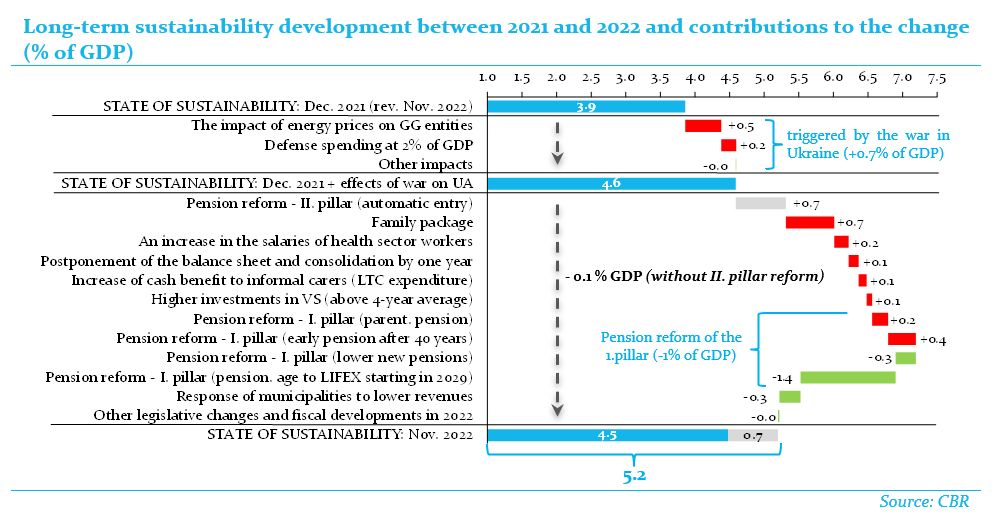

- The level of the long-term sustainability indicator is estimated to remain in the high-risk zone; in order to achieve the long-term sustainability, revenues would need increase and/or expenditures decrease by more than 6.4bn euros (5.2% of GDP). The situation is partially driven by external factors, especially Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the energy crisis, which contributed 0.7% of GDP to the deterioration in sustainability of public finances. Another 0.7% of GDP came from the introduction of the automatic entry to the second pension system pillar, although the Council evaluates its introduction positively[4].

-

- Adjusted for the aforementioned factors, the long-term sustainability of public finances will improve by 0.1% of GDP. The major contribution to this improvement comes from the pension system reform (1% of GDP) and expected savings by local governments (0.3% of GDP). By contrast, the remaining government measures worsen the sustainability of public finances by 1.2% of GDP. The Council, therefore, points out that, without the pension system reform, the presented general government budget has a negative impact on the long-term sustainability because the pension reform savings will only be felt after the budget period.

- Adjusted for the aforementioned factors, the long-term sustainability of public finances will improve by 0.1% of GDP. The major contribution to this improvement comes from the pension system reform (1% of GDP) and expected savings by local governments (0.3% of GDP). By contrast, the remaining government measures worsen the sustainability of public finances by 1.2% of GDP. The Council, therefore, points out that, without the pension system reform, the presented general government budget has a negative impact on the long-term sustainability because the pension reform savings will only be felt after the budget period.

- In the medium term, the CBR believes the main objective of the government should be to stabilise debt and create conditions for its further reduction by bringing deficit below the 3% of GDP limit and safely reducing the high risk of long-term sustainability to the medium risk zone.

- The Council positively evaluates the set budgetary objective of decreasing deficit to7% of GDP by 2025. If met, it would provide room for reduction of (net) debt and the long-term sustainability of public finances could improve by 1.4% of GDP and enter the medium risk zone (the long-term sustainability indicator of 3.8% of GDP), This would eliminate the permanent negative effect of Russia’s aggression on public finances. In order to achieve both recommended objectives by 2025, it would be necessary to reliably specify additional consolidation measures in the amount of approximately 2% of GDP, according to the CBR.

- By delaying the introduction of expenditure ceilings, the measures (deteriorating balance) approved before the adoption of the ceilings will not have to be funded in a permanent manner. As a result, the overall level of expenditures for 2024 and 2025 has increased compared to a scenario under which the expenditure ceilings would have been adopted at the beginning of the budgetary process. The government’s target deficit of 2.7% of GDP for 2025 would be in line with the ceilings if the methodology proposed by the Council is applied. In 2023, if there was a positive economic growth, the expenditure ceilings would require structural consolidation of 0.2% of GDP instead of 0.5% of GDP owing to the adoption of legislation improving the long-term sustainability beyond the effects of the budget. If GDP falls, expenditure ceilings do not apply.

- In addition to domestic investments that have undergone a “zero-based budgeting” reform in the recent years, the Value for Money principle should be applied more intensively to other economic policies, as well[5].

[1] Despite its repeated requests, the Council has not received any comments on the proposed methodology since the meeting of 14 July 2022.

[2] After this deadline, the government would be obliged to block 3% of selected government expenditures and immediately ask the parliament for a vote of confidence. At the same time, it should draw up a proposal for a balanced general government budget for 2024, containing no increase in expenditures.

[3] The draft budget plan presents two objectives for 2024: 1) a balanced budget that formally complies with the applicable sanctions under the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act; and 2) a deficit of 3.4% of GDP which, according to the Ministry of Finance, requires structural consolidation by 0.5% of GDP pursuant to the Stability and Growth Pact rules and is more realistic in terms of the necessary size of measures.

[4] Since the long-term sustainability indicator covers a period of 50 years and the benefits of lower payments from the 1st pillar to the persons concerned will for the most part accrue after this interval (and are therefore ignored from the 50-year-based calculation), the long-term sustainability indicator estimates a deterioration of 0.7% of GDP. If a longer time framework was taken into account, the impact on sustainability would be lower.

[5] The Ministry of Finance, and/or its Value for Money Unit, currently assess all investment projects of ministries and their organisations exceeding 1 million euros irrespective of the source of their funding. Assessment of smaller projects over 1 million euros was introduced by a government resolution (UV-22129/2020) at the end of 2020 and, compared to large projects, is considerably simplified.