Summary

The evaluation report on the compliance with the fiscal responsibility and fiscal transparency rules annually assesses, always by 31 August, the compliance with the rules under the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act[1] for the previous year. In addition to evaluating the development of long-term sustainability of public finances, the most significant objective pursued by the act, it also assesses compliance with the constitutional debt limit, as well as other statutory obligations, especially in the area of information disclosure, local government debt, and the funding of local governments’ competences.

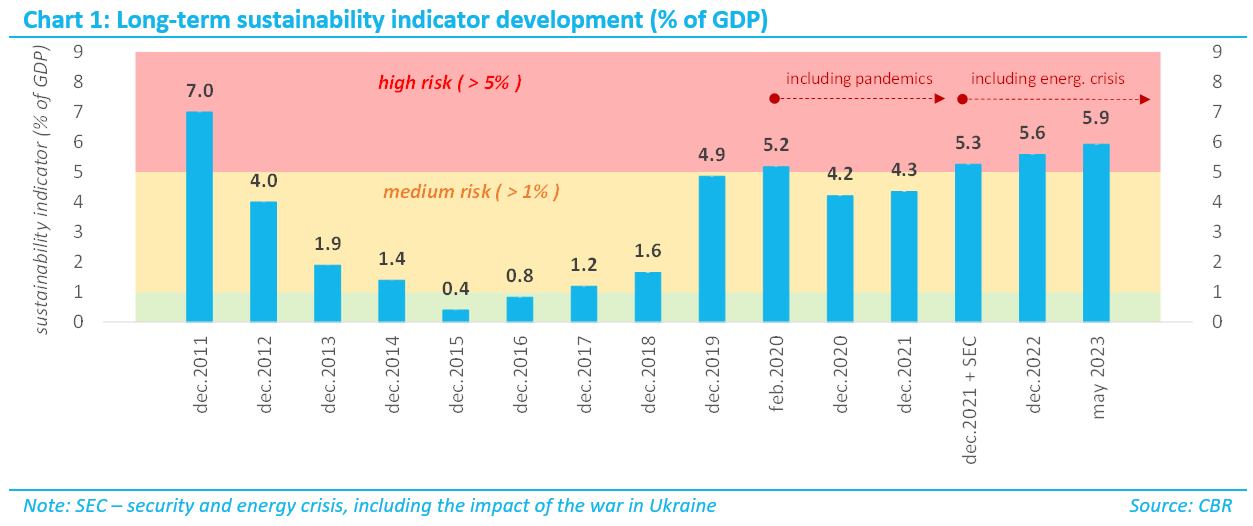

Long-term sustainability of public finances

The key objective of fiscal responsibility is to achieve sustainable public finances. The protection of long-term sustainability of Slovakia’s economic performance, taking into account the compliance with the principles of transparency and effectiveness of public spending, was enshrined in an amendment to the Constitution of the Slovak Republic[2] in 2020.

In its evaluation[3], the Council noted that the long-term sustainability of public finances, taking into account the most recent medium-term balance estimate of May 2023, has not been achieved. The long-term sustainability indicator reached 5.9% of GDP, which implies that public finances are in the high-risk zone. Therefore, a permanent revenue increase and/or expenditure reduction of EUR 7.6 billion would be needed to ensure long-term sustainability.

Given the poor state of public finances – affected also by external factors beyond the government’s control (the security and energy crisis) in addition to the adopted measures having a negative impact on the balance, the government should start working as soon as possible towards improving sustainability. In addition, the necessity of improving the long-term sustainability is augmented by the current high level of gross debt which is now, for the third year in a row, above the highest sanction bracket of the debt brake. In the medium term, even the estimate of an exceptionally strong inflation effect, along with the projections of real economic growth, are not expected to outweigh the very unfavourable outlook for public finances. Without taking additional consolidation measures, the current debt level will pose an increasing risk to the sustainability of public finances. It is therefore essential to prepare and implement a credible plan for a gradual, albeit reasonably ambitious consolidation of public finances over the medium term.

Long-term sustainability could also be improved with the contribution of an effective implementation of expenditure ceilings. In fact, the expenditure ceiling for 2023 does not constitute a binding rule due to an exemption currently applied as a result of the rules under the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact; however, as from 2024, when this exemption is expected to expire, the ceilings could secure a gradual improvement in long-term sustainability.

It should be added, though, that compliance with expenditure ceilings, in and of itself, at the minimum level required by law for improving the long-term sustainability[4] will not be sufficient for stabilising the debt in the medium term[5] and, from this perspective, the consolidation of public finances should be more ambitious.

The current wording of the constitutional act has not provided sufficient protection of long-term sustainability in particular due to the formal approach of governments, as well as of the parliament, when it comes to the fulfilment of debt brake sanctions; therefore, it would be advisable to amend the constitutional act in a manner that reflects the current debt trends and the need for effective liquidity management while at the same time ensuring that the debt brake combined with expenditure ceilings become an effective instruments for improving long-term sustainability. For this reason, it was with great regret that the Council took note of the fact that, after two years of delays, the vote on an amendment to the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act, which had been prepared for quite some time, was put off to the next election term. The promises that the debt brake would be updated along with enacting the national fiscal responsibility rules (including expenditure ceilings) within a single constitutional law have thus not been met.

The Council warns that the current situation also translates into a lack of synergy between the debt brake sanctions and expenditure ceilings, and thus the intended remedial effects of the national rules on public finances could be left unused.

Fiscal responsibility rules

In order to achieve long term sustainability of public finances, the law assumes the existence of expenditure ceilings and the general government debt limit (the so-called debt brake). Both of these instruments are expected to contribute to achieving the long-term sustainability of public finances.

General government debt limit

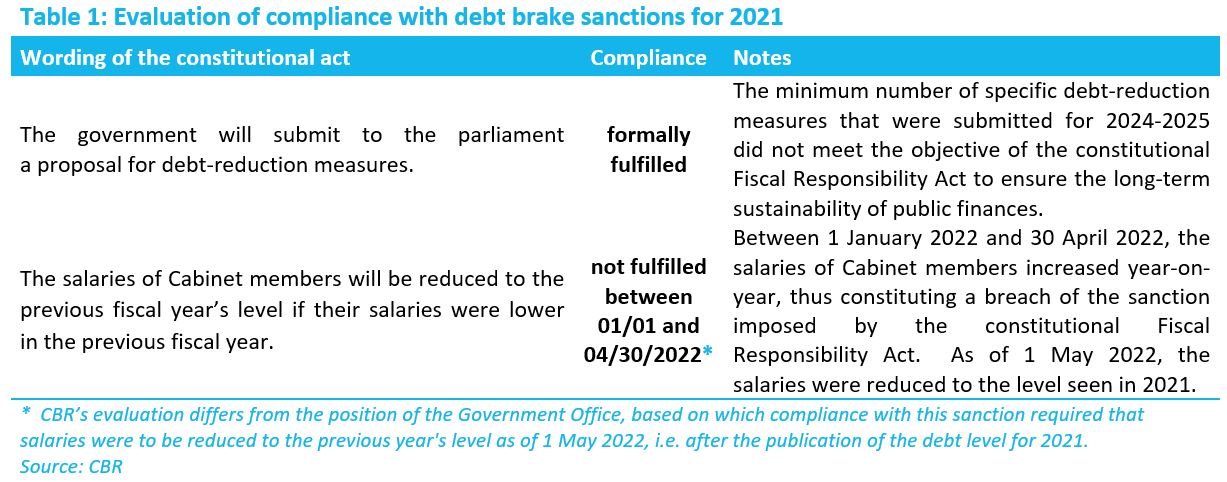

The debt-to-GDP ratio in 2021 and 2022 has exceeded the highest debt brake level, i.e., surpassing the fifth sanction bracket[6]. Based on data published by Eurostat in October 2022, the debt reached 61.0% of GDP at the end of 2021 and, based on preliminary[7] data from April 2023, 57.8% of GDP at the end of 2022.

As the 24-month exemption from the application of stricter sanctions under the constitutional act[8] has expired on 5 May 2023, the debt level for 2021 was only subject to the sanctions applicable to overrunning the second sanction bracket of the debt brake while the exemption was still in effect.

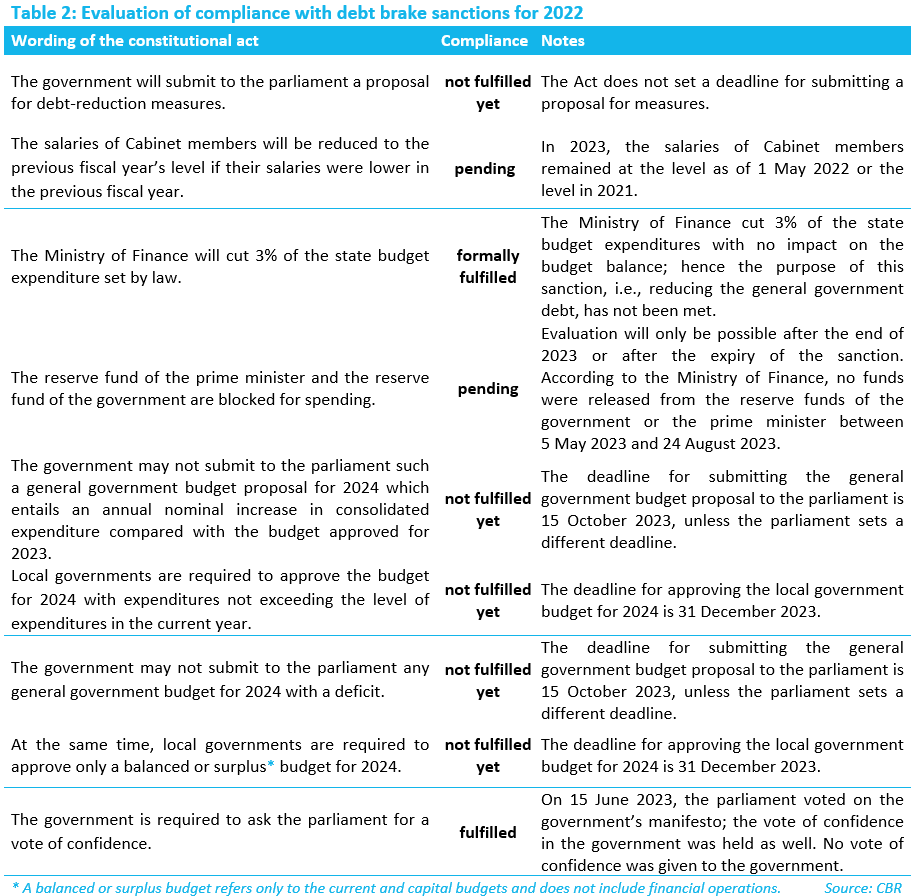

The debt level achieved for 2022 is currently associated with sanctions resulting from overrunning all of the five sanction brackets of the debt brake. The debt brake sanctions are applied cumulatively, starting with the sanctions for overrunning the second bracket up to the highest sanction bracket.

Compliance with the above sanctions will also be affected by the approval of the government’s manifesto after the early parliamentary elections to be held on 30 September 2023. The approval of the government’s manifesto and the vote of confidence in the government will re-trigger the 24-month exemption from compliance with the sanctions applicable between the third and fifth sanction bracket of the debt brake.

Despite the high levels of the general government debt, which have been continuously hovering above the highest sanction bracket of the debt brake since 2020, compliance with the sanctions has recently been only formal, with a minimum impact on the reduction of the general government debt:

- The government submits to the parliament, on a repeated basis, a document concerning the justification of the general government debt level and a proposal for debt-reduction measures. In its opinions[9] in the past, the Council has been pointing out that this document does not contain a sufficient number of specific debt-reduction measures, which means that, in reality, the purpose of sanctions, i.e., reducing the general government debt below the sanction brackets, is not met. Moreover, the latest proposal was submitted to the parliament with a 10-month delay after the publication of the debt level; such a timeframe is not reasonable given the size of the debt.

- In May 2023, the government cut 3% of total state budget expenditure, but did so only for items with no impact on the general government balance. Again, such compliance with the provision of the constitutional act was only a formal one, with no impact on the reduction of the general government debt whatsoever.

Over the medium term, the CBR estimates[10] that, without additional measures, gross debt will cumulatively increase by 7.3 p.p. from 57.8% of GDP at the end of 2022 to 65.1% of GDP in 2027. The estimated increase in general government debt is mainly due to very unfavourable developments in the structural primary balance. The highest sanction bracket based on the debt brake will start at 50% of GDP in 2027, which means that the debt would be 15.1 p.p. above this threshold. Taking into account the 2-year exemption from the application of the most stringent sanctions of the debt brake following the approval of the new government’s manifesto after the early general elections held in the autumn, there is a serious risk of a renewed need to present a balanced general government budget proposal with no increase in expenditure for 2026.

Public expenditure ceilings

In addition to the debt limit, the constitutional act had from the very beginning envisaged introducing an operative fiscal management tool – expenditure ceilings – as an imperative component of responsible fiscal performance. Since the adoption of the constitutional act, it took more than ten years to make the public expenditure ceiling – effective from 1 April 2022 – the key budgetary instrument to achieve the long-term sustainability of public finances. The ceilings were to be applied for the first time with regard to the general government budget for 2023-2025; however, this did not happen due to the absence of an agreement on the ceiling calculation methodology. The Ministry of Finance and the CBR reached an agreement on the methodology for calculating, updating and evaluating compliance with the expenditure ceiling as late as on 22 December 2022, only a few hours after the approval of the 2023 State Budget Act in the parliament. Immediately after reaching the agreement, the CBR calculated and submitted to the parliament the public expenditure ceilings for the years 2023 to 2025. The submitted ceilings were approved by the parliament on 1 February 2023. After the parliament passed an amendment to the Act on General Government Budgetary Rules and, subsequently, the public expenditure ceilings, the situation encompassing an infringement of the constitutional act[11] has been remedied. On 22 December 2022, the parliament also approved an exemption from the obligation to bring the budget in line with the expenditure ceiling for as long as the European general escape clause remains activated. Therefore, in view of the currently applicable general escape clause activated by the European Commission, the government is not required to align the 2023 budget with the ceiling approved by the parliament.

Therefore, the public expenditure ceiling is not contributing this year to improving the long-term sustainability of public finances as the primary objective of the rule. The first ceilings were, unusually, calculated in the middle of the election term and, considering the fact that a number of measures significantly deteriorating the development of public finances in the medium term[12] had been adopted in the course of 2022, the consolidation of public finances as required by the ceilings was based on a worsened baseline. At the same time, due to the general escape clause being in force during 2023, the government is not required to bring the budget in line with the applicable ceiling. As a consequence, 2023 saw the adoption of a number of other legislative changes causing a permanent increase in expenditure (e.g., subsidies for lunches in schools, support for research and innovation, the School Act) without the need to compensate for their impacts, which is likely to result in significantly overrunning the ceiling[13] valid for 2023. Any consolidation of public finances that is likely to take place in the future will be based on a starting position which incorporates all the measures adopted between 2022 and 2023.

Enacting the expenditure ceilings by a constitutional law would considerably strengthen their binding nature, as originally envisaged under the draft amendment to the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act. It would significantly reduce the risk of this instrument being vulnerable to changes that could undermine or completely cancel its capability to ensure the effective fulfilment of the main purpose of expenditure ceilings.

Specific provisions for local governments

The rules applicable to local governments are aimed at separating the responsibility for their solvency from the state, securing the funding of their new tasks by the state and preventing the excessive indebtedness of local governments. For this reason, the following three aspects are evaluated: 1/ whether the state has intervened financially to safeguard the solvency of local governments; 2/ whether the state has assigned new tasks and competencies without providing adequate financial coverage, and 3/ the amount of the local government debt.

- The CBR notes that the state did not financially intervene to safeguard the solvency of local governments. In 2022, local governments did not receive loans from the state, that would improve their financial performance[14]. However, it is still necessary to adopt legislative changes that will set the rules even in this area in order to prevent any selective preferential treatment of local governments while avoiding their insolvency in future.

- In the course of 2022, according to available information, the local government sector was not assigned any new tasks which would have required funding from the state[15]. However, there was a significant intervention affecting the revenue from shared taxes (an increase in the child tax bonus), the impacts of which had not been sufficiently assessed beforehand by the government and parliament. According to the constitutional act, the obligation to ensure adequate financial resources does not apply to changes in the existing competencies of the local governments that have no significant financial effects; there are mechanisms in place which a local government may use to obtain resources in another way (e.g., by increasing taxes[16] or shifting the burden of costs on recipients of services)[17]. The failure to use these mechanisms may indicate that problems with funding are less urgent.

However, 2022 saw submissions and rulings of the Constitutional Court regarding the so-called “family package” measures, water supply connectors and environmental burdens which are important in terms of adequate funding for local governments. The rulings of the court indicate that, in line with the principle of transparency and efficiency, any changes which affect the funding of local governments must always be subject to a standard review procedure. It is also necessary to strictly observe and monitor the effects of measures so that the central government authorities do not create additional burden on local governments’ budgets without identifying such impacts in impact clauses, while at the same time preventing that new tasks are shifted (be it in terms of exercising the original powers or the powers conferred on local governments) onto local governments without providing adequate financial coverage[18].

- Administrative proceedings on the imposition of fines for 2021 on local governments with excessive debt[19]were closed. While all self-governing regions ended up with debts below the prescribed limit, the fines were imposed on 15 of the 43 initially identified municipalities after legislative exemptions had been considered and reported values cross-checked. There are currently 28 municipalities at risk of fine for 2022; the values they reported are now under review. Further 46 municipalities were contacted because they had not submitted the required financial reports. In 2022, too, the debts of all self-governing regions stood below the statutory limit. The Ministry of Finance assessed the compliance with the local government debt rule, with the possibility to impose a fine, for the first time for 2015, but not a single evaluation has been disclosed so far. The CBR recommends that the Ministry of Finance disclose[20] all information related to reviewing the size of local government debts, and imposing the fines, in a transparent manner.

As from 1 August 2023, an amendment to Act No. 583/2004 Coll. on the Local Government Budgetary Rules entered into force, introducing the possibility to relieve the local government of its debts where they cannot be fully recovered under receivership, which means that, after 20 years, the outstanding amount of the debt will become unenforceable[21]. Despite the fact that, in its report, the CBR recommended the adoption of measures aimed at restructuring the debts of municipalities (without providing a specific proposal), the approved solution seems to be problematic in terms of legislation, as the Ministry of Finance presented in its opinion. According to the Ministry of Finance, such a legislative change has no backing in terms of its practical application and is incompatible with the legal system of the Slovak Republic[22], while there is a risk of lawsuits against the Slovak Republic by creditors if unpaid debts become unenforceable after 20 years.

Fiscal transparency rules

The fiscal transparency rules defined by the constitutional act were fulfilled almost in full extent. Macroeconomic and tax revenue forecasts were approved by competent independent committees and published within the deadlines specified in the constitutional act. The 2023-2025 general government budget contained all the data required by law, save for the information about a majority of companies with capital participation of the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic (healthcare facilities and Všeobecná zdravotná poisťovňa health insurer). The summary annual report for 2021 contained all the data required by law.

In addition to the requirements defined by law, the CBR also assesses the budget transparency in terms of comprehensibility and quality of the information contained in the assessed documents, consistent application of the ESA2010 methodology, and the measure of parliament’s control over the approval and fulfilment of the budget. These areas were also covered by the CBR’s recommendations contained in its August 2022 report, in which case, however, no progress has been made, apart from a slight improvement in the comparability of the budget with reported data.

The continued efforts to streamline public investment through zero-based budgeting and to improve CBR’s access to data from other institutions, which is necessary for fulfilling its mandate and high-quality analytical outputs[23], can be regarded positively.

According to the CBR, the most important ongoing issues, resolving which could lead to further qualitative enhancements in fiscal transparency and the entire budgeting process, are as follows:

- Multiannual budgeting is still absent. The budget proposal is compiled in accordance with the budgetary objective only for 2022, but not for the years to follow. The key fiscal indicators (structural balance, gross and net debt forecasts) were repeatedly presented under the assumption of meeting the budgetary objectives with no measures specified, thus showing the public finances in a better shape than they actually are.

- In compiling the expenditure side of the budget proposal, the focus should be more on the no-policy-change scenario for the next three years, as foreseen in the Act on the General Government Budgetary Rules[24]. At present, the budget proposal is presented in this manner only with regard to the expenditure of health insurance companies, which allows for a transparent assessment of assumptions for drawing up the health sector budget, including the impacts of implemented measures. The same procedure should also be extended to other areas.

- The CBR has repeatedly noted that the existing legislative framework governing the budget approval procedure in the parliament does not fit the scope and content of the documents that are being approved. The approval of a cash-based state budget (alone) by the parliament for the upcoming year[25] is based on a historical tradition, but is no longer sufficient to capture the key monitored parameters of public finances and all changes in public finances in accordance with the European standards defined by the ESA2010 methodology, including the expenditure ceilings.

- Important legislative changes are repeatedly adopted by the parliament even after the government approves the budget proposal and submits it to the parliament. In terms of transparency of tax revenues presented in the budget, this approach cannot be considered correct. Less transparent decision-making as regards inclusion of measures in the general government budget makes it difficult to evaluate the budget in terms of compliance with the declared objectives for the budget balance. In addition, several tax measures have been adopted within a fast-track procedure, many of them as amendments to unrelated laws. Such approach is not in line with the Act on the Rules of Procedure of the National Council of the Slovak Republic[26].

- Better information could be provided for state-owned enterprises. A brief commentary on expected economic results of individual enterprises would make it possible to better assess any potential risks arising from the performance of enterprises owned by the state, either directly or through MH Manažment, a.s.

- The information value of the net worth indicator could be enhanced by the valuation of net worth components not yet quantified. A broader analysis of the impact of government measures on the net worth will require the adoption of appropriate technical arrangements for the collection of data and the definition of methodology (in collaboration with the CBR) for linking the net worth change to the budget balance.